Introduction

Shadertoy.com is an online community and tool for creating and sharing shaders through WebGL, used for both learning and teaching 3D computer graphics in a web browser.

The approach in Shadertoy is to produce images with minimal data input to the graphics pipeline where most of the heavy lifting is performed directly in the fragment shader. The vertex shader in this case is only used to process a full-screen quad which functions as the canvas for these visual effects. This is not always the most ideal way of doing 3D-programming but if you want to play around with a lot of math and get creative, you’ve come to the right place.

In this post, I summarize the discoveries I’ve made along the way and updates to Luz that were necessary to implement Shadertoy support.

Plugin Demo

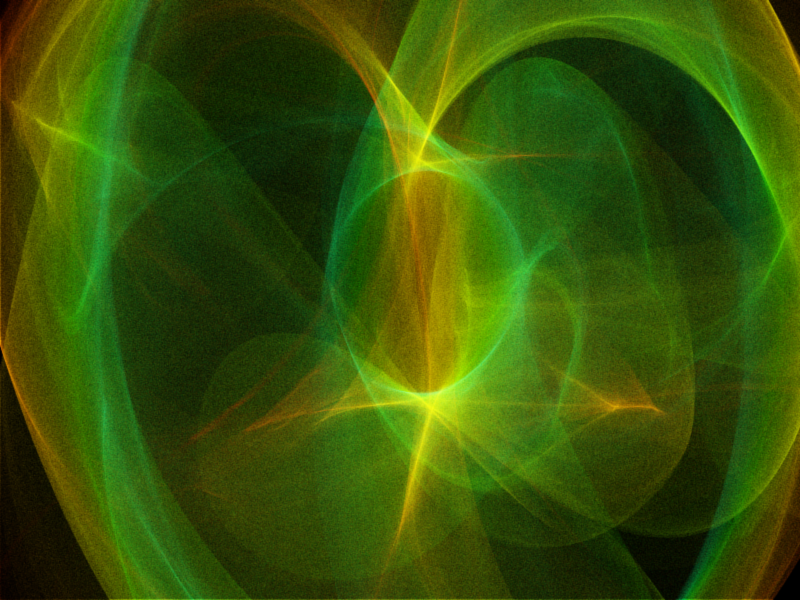

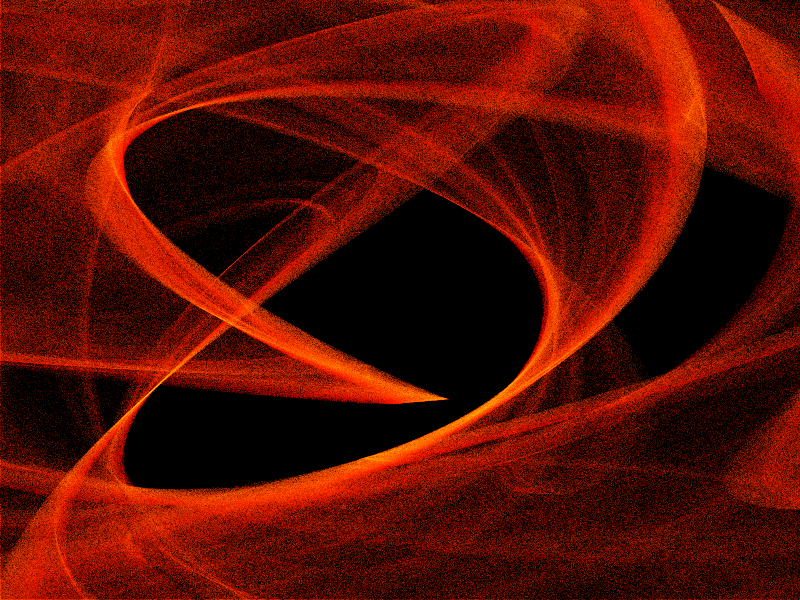

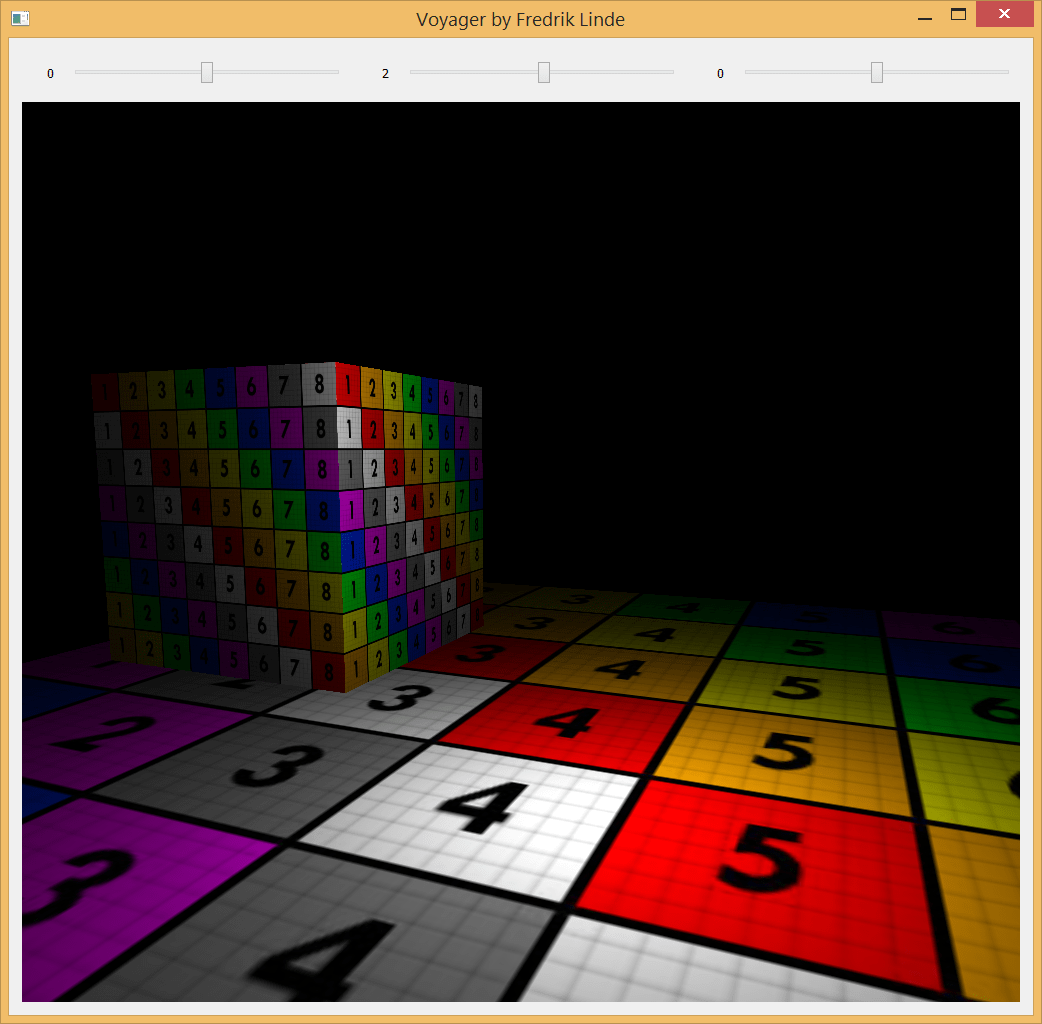

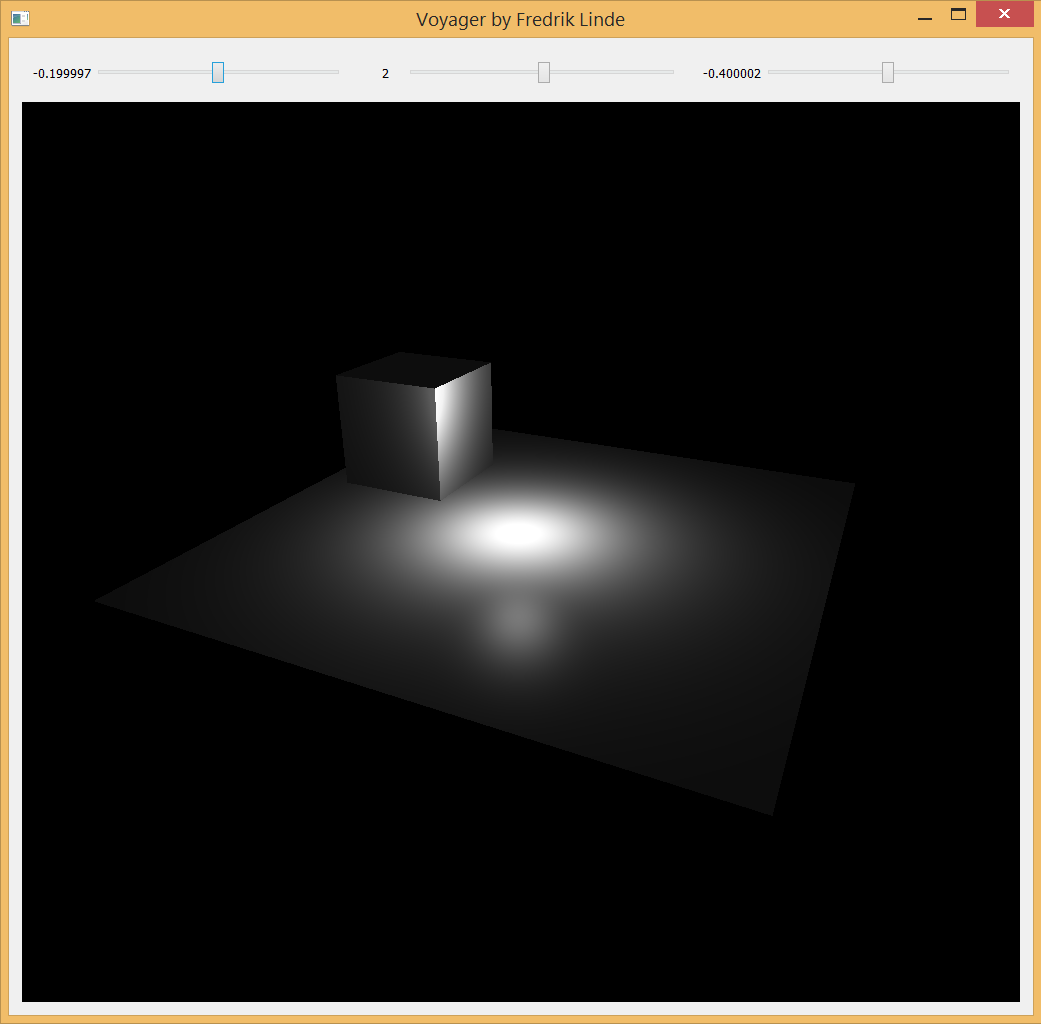

Here is a demo with a couple of shaders from Shadertoy that this plugin can interpret and render using Luz. They are all listed below in order, all rights belong to their respective owners:

As you can see, many shaders written for Shadertoy features input support and this data had not yet been forwarded to previous plugins. Alongside with mouse position updates, input callbacks within Luz are now also forwarded to the plugins. This enables us to create interactive turntable cameras or move the position of the camera.

Plugin Dependencies Localization

If you have a DLL that links to dependencies from the same folder, such as other dynamic link libraries, then it’s necessary to add that DLL directory before attempting to call LoadLibrary. Otherwise you will be given the error code 126 from GetLastError, which translates to ERROR_MOD_NOT_FOUND. This could be somewhat misleading at first if your targeted DLL file does exist at the specified location, but it’s in fact the dependency of the plugin that cannot be found.

const size_t pos = path.find_last_of("\\");

SetDllDirectory(path.substr(0, pos).c_str());

pluginHinstance = ::LoadLibrary(path.c_str());

This is an easy mistake to make and I was naive to think that LoadLibrary would be able to resolve this on its own by looking in the same folder the DLL was loaded from. I found the following statement from the official documentation which gave me a better understanding of the issue:

If a DLL has dependencies, the system searches for the dependent DLLs as if they were loaded with just their module names. This is true even if the first DLL was loaded by specifying a full path.

Hence, this is why we need to make the call to SetDllDirectory.

OpenGL Compensations

Unlike Vulkan where headless rendering is possible, OpenGL requires a window to create the context. It’s not really a problem since we can specify to GLFW to create the window as hidden so we will never be able to interact with it. Once we have set it up, we only need the window to swap buffers between render calls.

glfwWindowHint(GLFW_VISIBLE, GLFW_FALSE); window = glfwCreateWindow(width, height, title, monitor, NULL);

Since OpenGL also defines bottom left corner of the screen as (0, 0) unlike in other API:s where (0,0) is located in the upper left corner of the screen, I felt the need to provide a way to compensate for this without tying myself up to any API conventions. Luckily, ImGui::Image lets me provide the coordinates for the corners of the image and I decided to let the user define what positions the corners should be. This means we can render an image as usual regardless of the convention used by the underlying API in the plugin and then Luz compensates it for final presentation.

"Framebuffer": {

"UV0": {"x": 0.0, "y": 1.0 },

"UV1": {"x": 1.0, "y": 0.0 }

},

Execution Warnings

Before I started writing the Shadertoy plugin, Luz had no concept of criticality levels in terms of return values from the various stages of execution. If something failed in the plugin, Luz would unload the plugin and return the latest error message.

In this case when you’re reloading shaders on the fly, it’s only a matter of time before you slip and accidentally write some invalid syntax (it’s kind of the whole point to allow for experimentation). Just because a shader could not be compiled, I don’t want Luz to unload the plugin but rather just print the latest error message and keep the plugin active. So it was about time that I introduced some criticality levels:

- Success: Everything executed as expected and the plugin continues to feed Luz with image data.

- Warning: Something of concern was detected during execution and requires the user’s attention. Plugin will continue to execute without the guarantee of correct image presentation or optimal performance.

- Failure: A critical error was detected and the plugin cannot execute properly until it has been fixed.

While the criticality levels themselves don’t always guarantee proper error handling, it can be a guiding tool for troubleshooting along with the messages recorded in the log. Below is an example of how the color coding looks like in the log:

Future Work

In order to reach full compatibility with Shadertoy, my plugin will have to increase its number of iChannel uniforms to a total of four. They are currently only interpreted as sampler2D uniforms but since I’m looking to support cube maps as well, I will work on adding samplerCube uniforms for the next version. Another concept in Shadertoy that I haven’t implemented yet are buffer stages which can serve as input into any of the four iChannel slots to allow for more advanced and longer chains of computations.